AFWG shall not bear any responsibility for any content on such sites. Any link to a third-party site does not constitute an endorsement of the third party, their site or services. AFWG also makes no warranties as to the content of such sites.

Would you like to continue?

Professor Arunaloke Chakrabarti

Head

Department of Medical Microbiology

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research

Chandigarh, India

Candida auris was first described in 2009 following isolation of the pathogen from the external ear canal of a patient in Japan; identification of the pathogen was only possible by sequencing the organism’s genome.1 It was soon detected in Korea2 and, in less than a decade, emerged in all 5 continents of the world.3,4 Its multidrug-resistant clonal strains that appear to be nosocomially transmitted is reason for concern.

The prevalence of C. auris infections remains inconclusive. A study in India which analyzed samples of patients from 27 intensive care units reported a prevalence of 5.3%.3 Further analysis to ascertain unique features of C. auris revealed the following risk factors5:

The authors concluded that patients with sepsis, undergoing invasive management for longer durations and exposed to antifungal agents should be investigated for C. auris candidemia.5

Characteristics of C. auris

C. auris is commonly misidentified as other species because of the lack of a reference database for several laboratory commercial phenotypic systems. Currently, accurate identification can be performed using matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)6 following a database update, as well as with DNA sequencing.7 C. auris may be suspected by its growth at 42°C but not in the presence of 0.01% or 0.1% cycloheximide.8 Another phenotypic feature of the pathogen is its ability to ferment dextrose, dulcitol and mannitol.9 However, the isolate can only be confirmed by sequencing.

In vitro properties of C. auris include the following:

Studies from Public Health Laboratory, UK, have found that C. auris presents in 2 types, aggregate-forming and non-aggregate–forming isolates.11,12 The non-aggregative isolates were found to be more pathogenic than the other type and has better biofilm-forming capability. A study also found C. auris to be more virulent than other key pathogenic non-albicans Candida species but comparable to that of C. albicans.11 However, an unpublished study showed higher biofilm formation in non-aggregative C. auris compared with C. albicans, suggesting variation in properties that is yet to be understood.

Multidrug resistance in C. auris

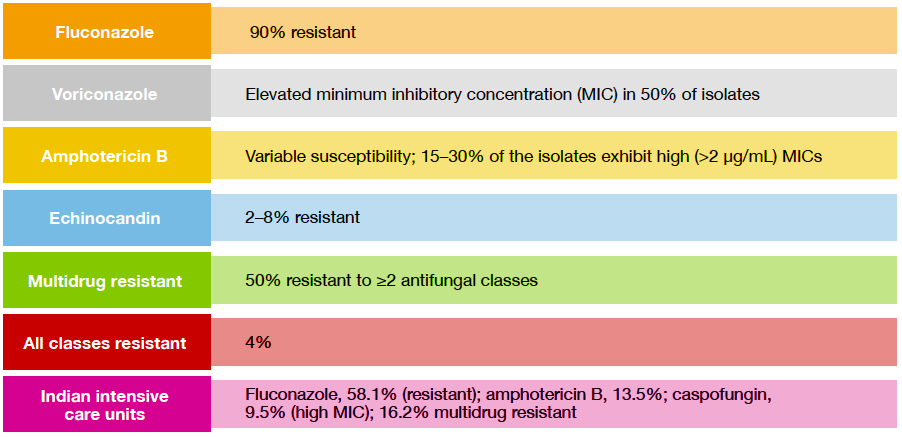

C. auris is inherently resistant to all classes of antifungal agents, with alarmingly high rates of mortality and therapeutic failure reported worldwide.13 Recent reports show extremely high resistance to fluconazole and elevated MIC against voriconazole, as well as against other drugs (Figure).3,14,15

Figure. Drug resistance in C. auris in Asian countries

Treating C. auris infections

At present, no consensus exists on the optimal treatment of C. auris candidemia. Echinocandins remain as first-line therapy, however, caspofungin has been shown to be inactive against C. auris biofilms. Flucytosine may be used for renal or urinary tract infections, whereas posaconazole and isavuconazole have shown excellent in vitro activity against C. auris. New drugs SCY-078 and pulmocide are anticipated to exhibit potent antifungal activity against C. auris isolates.

Prevention and control of outbreak

Surveillance of C. auris colonization in an Indian hospital showed that by Day 4, all patients in the ICU were colonized although none were at the time of admission. Persistence of C. auris in the hospital environment were mainly observed in the hands of healthcare workers, equipment such as ventilator, temperature probes and echocardiography leads, as well as bed surfaces, blankets and linen. Decontamination was successful using chlorhexidine body wash, oral nystatin tablets, and hand washing with soap and water and various disinfectants, however, success depended on the use of correct methods and sufficient exposure time of the agents to the infected surfaces.

Red flags of C. auris candidemia

In summary, C. auris infection should be considered in patients in the ICU or high-dependency units, those who have been transferred from another hospital following a long stay, and patients receiving multiple interventions and with prior antifungal exposure. Additionally, the identification of the pathogen as other Candida species via a commercial system and finding that the pathogen appears to be resistant to fluconazole and exhibits high MIC to voriconazole are also red flags of C. auris infection.

References