AFWG shall not bear any responsibility for any content on such sites. Any link to a third-party site does not constitute an endorsement of the third party, their site or services. AFWG also makes no warranties as to the content of such sites.

Would you like to continue?

Dr Atul Patel, MD, FIDSA

Chief Consultant and Director

Infectious Diseases Clinic

Vedanta Institute of Medical Sciences

Ahmedabad, India

Clinical presentation

A 68-year-old patient with diabetes and chronic kidney disease was presented with fever, progressive nasal ulcer with crusting and painful palatal ulcer (Figure 1A). His work up for fever showed bilateral enlarged adrenal glands on abdominal CT scan. Biopsy from the palatal ulcer showed intracellular yeasts consistent with a diagnosis of histoplasmosis (Figures 1B & 1C). As Histoplasma antigen test was not available, a serum galactomannan test was conducted and yielded 3.48 ng/mL.

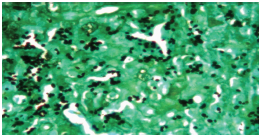

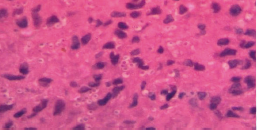

Figure 1. Clinical presentation of the patient with progressive nasal ulcer with crusting and painful palatal ulcer (A); and silver stain (B) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain (C) of the biopsy sample from the palatal ulcer

A

B

C

The patient was treated with oral itraconazole and had a good clinical response with marked regression in nasal and palatal ulcers (Figure 2) and a decrease in serum galactomannan level (2.48 ng/mL) after 6 weeks of therapy. The patient had complete clinical response after 7 months on antifungal treatment with further decrease of the serum galactomannan level to 1.45 ng/mL. His antifungal treatment was stopped at 9 months when the serum galactomannan level was at 0.68ng/mL. The patient had no sign of relapse 3 months follow-up after treatment completion. This case showed positive correlation of serum galactomannan levels with clinical response for histoplasmosis.

Figure 2. Marked regression in the nasal and palatal ulcers after 6 weeks on oral itraconazole therapy

Discussion

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis is challenging as serological tests are not reliable, and culture is positive in only 50–70% and takes several weeks before it becomes positive.1

Detection of Histoplasma antigen from serum, urine and CSF is a sensitive and specific assay for diagnosing histoplasmosis but it is not available in many parts of world, including India. It may also be negative in localized diseases and only positive in progressive disseminated form of histoplasmosis. Histoplasmosis shares many clinical presentations and radiological features of tuberculosis, eg, fever of unknown origin, lymphadenopathy, adrenal gland enlargement, pulmonary nodules, etc. In regions of high tuberculosis prevalence, like India, histoplasmosis is generally not suspected. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis is generally made from the demonstration of intracellular yeasts in histopathological examination.

Positive Aspergillus galactomannan test can be used as a surrogate marker of Histoplasma infection. The minimum cutoff threshold for serum galactomannan to detect histoplasmosis is 0.4, giving a sensitivity of 82.1% and specificity of 100%.2 False-positive results from Aspergillus galactomannan assay has been reported in solid organ transplant recipients with histoplasmosis.3 Cross-reactivity between Histoplasma antigen and Aspergillus galactomannan has also been described in an HIV-infected patient with histoplasmosis.4 Therefore, physicians need to differentiate the 2 disease entities, especially when it comes to treatment decision making. In countries where Histoplasma antigen assay is not available, the cross-reactivity between Histoplasma and galactomannan antigens could be helpful surrogate marker for making a diagnosis of histoplasmosis in appropriate clinical and laboratory settings.

Clinical pearls

Highlights of the Medical Mycology Training Network Conference, December 1–3, 2017, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

References